Taste Is the Lack of Appetite by graft

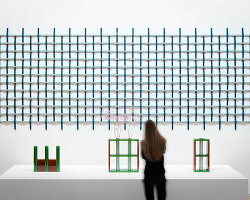

The Aedes exhibition Taste Is the Lack of Appetite marks the 25th anniversary of GRAFT, an internationally active architecture firm known for its distinctive approach to design and social engagement. designboom attended the exhibition’s opening, during which GRAFT partners guided us through the two-space display and they generously shared insights into their unwavering curiosity for the unexpected, reflecting a design practice characterized by optimism and a passion for experimentation. A group of five individuals, each hailing from different backgrounds, complement one another, and together, they push the boundaries of traditional architecture and achieve intricate design solutions. The statement by the American art critic Dave Hickey that ‘Taste is the lack of appetite’ serves as a guiding principle for GRAFT’s work, hence the title. The firm embraces curiosity and passion when confronting challenges, fostering an open and innovative spirit rather than adhering to predefined architectural conventions.‘The importance of curiosity is maintaining a state of mind that allows you to discover something you weren’t actively looking for – that’s serendipity, and that’s what we live for,’ GRAFT shared with designboom.

The showcased projects encompass a diverse range of residential, mixed-use, and cultural buildings, each exemplifying the firm’s innovative design strategies. Additionally, the exhibition talks about ‘Architecture Activism’ and features the original prototype of their community-building project known as Solarkiosk. The Solarkiosk is an innovative intervention in remote African regions that provides clean solar energy, connectivity, and communication, all while promoting a sustainable, post-colonial social model. ‘All these kiosks add small dots of light and give people more time to communicate because this light in the night is extending the time,’ GRAFT partners explained. ‘We see communities using the energy to establish businesses like hair salons, creating job opportunities, and people becoming inventive, even opening small cinemas that broadcast news and sports events.’ They added, ‘It’s about recognizing a specific need, feeling the urge to intervene without having a client assign a task, and creating a solution from your own intrinsic motivation.’ Read the interview in full below!

video ©designboom

image ©Erik-Jan Ouwerkerk

interview with GRAFT partners AT AEDES ARCHITEKTURFORUM

designboom (DB): Can you tell us more about the exhibition title and how it reflects GRAFT’s design philosophy and approach? Is there a specific message you want to convey to the audience?

Wolfram Putz: The title of the exhibition is Taste is the Lack of Appetite, and it portrays our philosophy about looking at the world. You can have a feeling of certainty, a longing for what’s right and wrong, whatever you want to put a stable image for yourself or your architecture firm on. However, we think the opposite. We believe hunger for curiosity and reaching out for the unknown should be the perpetual philosophy and attitude towards architecture that we want to provide.

Lars Krückeberg: Conveying a single message through the title may be ambiguous. And that’s what we like. We like ambivalent things. It’s also in the name of our firm, graft. One message is that we live in times of real dynamics of cultural and global changes. And it’s not the time to have a good taste. It’s time to find real solutions. You have to be hungry to find them. And especially in architecture, because it combines so many aspects at the same time, it’s at the heart of our societies. We don’t have the luxury of having good taste; we need to find great solutions that hunger for looking for a wonderful solution that brings beauty and identity to our firm environments. That’s what interests us. And that’s what we think is needed these days.

Wolfram Putz: This is an exclusive concept, and we look at the world as an inclusive necessity, broadening to every person to all people to all cultures. And the taste is a training programme of saying, ‘this is good, this is bad, this is right, this is wrong; this should be done, or this should not be done.’ And this can be extremely limiting, and we don’t believe in that.

image ©Erik-Jan Ouwerkerk

DB: Could you explain what is the Solarkiosk project and its significance?

Thomas Willemeit: A good friend of ours had been trying to promote solar products in Africa, and together, we came up with the idea of advancing solar technology and energy in the region. We immediately understood that developing an extensive design strategy and master plan wasn’t feasible. Instead, we needed a small, controllable solution as a local intervention to bring a big change to rural areas. Our idea was to create an independent, little power station for rural communities that lacked access to electrical grids. The kiosk combines solar panels on the roof with local batteries and charging infrastructure. That way, we make sure that we harvest the sun to generate energy while providing locals with access to power. That means improving their lives by charging their cell phones, using solar lamps, and even running a local fridge, that every kiosk contains. It may also revolutionize our thinking so that we don’t believe so much in general master planning for a very long time top-down anymore. However, we have learned that some very small local interventions can create development from the bottom up. And this is something we need, especially in such local areas in Africa.

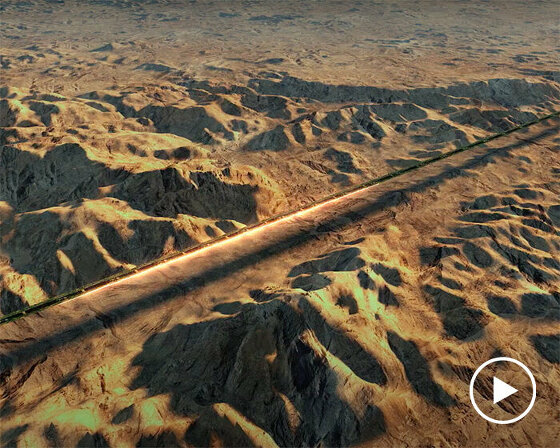

Sven Fuchs: Light was literally brought to darkness. When you look at this, for me, it is the most eye-catching picture of Africa and the world. When you view these night vision images, you can see that Europe and the US are shining bright, and you can see this road from Moscow to Sibiria. But when you look at Africa, apart from South Africa, it’s pretty dark, and all these kiosks add small dots of light and give people more time to communicate, not only electricity but time because this light in the night is extending the time. Looking back at European history, the presence of human-generated light during the night has been a driver for innovation. It has been a driving force for innovation in Europe and can similarly drive innovation in Africa.

©designboom

DB: What is the design process until its completion, and what services does it offer the communities? How do people embrace the structure?

Thomas Willemeit: We had the idea for the kiosk and made a little sketch, but we quickly understood that it required much more. So, we needed to find the right partners, develop precise technology plans for the kiosk, and, of course, secure financing. Therefore, if we truly wanted to bring this idea to life, it was evident that we had to establish a new company to build, implement, and run the kiosks. We started with our local company in Berlin and then gradually expanded into partner countries in Africa, beginning with Ethiopia and then Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Ghana. We were able to raise funds from foundations and donors from all over the world to finance over 200 kiosks that you can now find operating in local communities across Africa. What’s especially interesting for us is observing the next step happening locally. We see communities using the energy to establish businesses like hair salons, creating job opportunities, and people becoming inventive, even opening small cinemas that broadcast news and sports events. As a result, various pubs and small businesses have been created all around the Solarkiosks. So, at the end of the day, a completely different approach, starting with these small interventions, proved to be more successful than developing an overarching concept for an entire country. But to try out pilot projects and learning how these kiosks would work helped us to accelerate the rollout and the success of the Solarkiosks.

Thomas Willemeit: Working on these projects, you learn a lot about people, and, of course, there were some very interesting learnings. For example, in many cases, when we tried to find the right individuals to operate the kiosks, primarily women, the local women brought across both the responsibility and the capability to organize. We always ask our local partners to identify and propose five to ten people to run each kiosk. We would then conduct interviews, provide training, and, after a trial phase, allow them to run the kiosk completely responsibly on their own.

©designboom

DB: What is your vision for the future of the Solarkiosk?

Thomas Willemeit: There are many ideas, some of which have already been tried. I could name a few. There’s the possibility of the Solarkiosk, which allows people to implement and build local clinics at a very fast pace. Together with the Siemens Foundation, we were able to finance a larger solar clinic in one of the world’s largest refugee camps in Jordan at that time. Additionally, with the help of the Hope Foundation from the United States, we financed smaller solar clinics, which were built like larger entities. These four clinics were implemented in Bangladesh after we had an influx of refugees from Myanmar crossing the border into Bangladesh. There are numerous possibilities and endless opportunities to take the next steps. The intention was to allow all these creative solutions to be generated locally. This is maybe the most exciting aspect for us. As Europeans, we don’t have to implement everything and think it through from the beginning to the end. Instead, we can provide our knowledge and a deep understanding of local challenges to help with smaller interventions that enable local initiatives to grow on their own.

Sven Fuchs: We participate and enjoy seeing how it’s being built up, further developed, taken in new directions, adapted, and used in different ways, bringing new inspiration back to us. But the main idea is that with these 200 kiosks already out there, other people can take them, make changes, and adapt them for different purposes. And it brings joy to see that.

©designboom

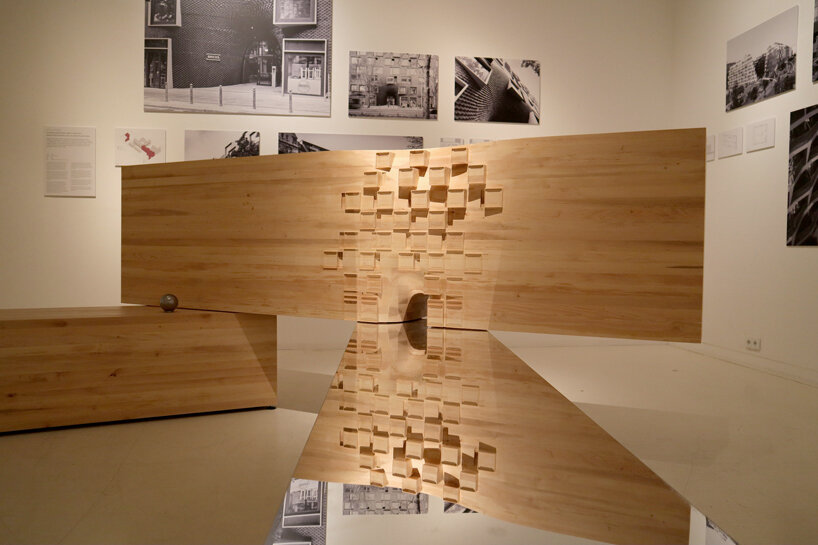

DB: in the exhibition, you mention six different buildings presented as concrete results of abstract design strategies, such as lofting, tracing, sectioning, weaving, etc. Can you describe how these design strategies have been applied in your projects and how they contribute to unique designs?

Lars Krückeberg: Each project asks different questions; if you ask back, you will have different answers. This means that each project should and will look different. Sometimes, you can apply a method as a tool to portray the essence of the project better. For instance, in the case of Charlie Living, a residential project where we tried to implement light and air into a densely designed space while also prioritizing green elements, we didn’t just aim to create an oasis on the ground but also wanted greenery to be integrated into the building’s facades. To achieve this, we employed the weaving method, as it best suited our goals. This method allowed us to design balconies that overlapped, providing enough space for trees to grow and receive ample light. Weaving was the best method to answer the specific requirements of this project. Similarly, other projects require different methods aligning with the desired narrative or essence in that area.

Sven Fuchs: Absolutely, it’s important to find out that there is not design strategy at the beginning, followed by the project or its outcome. Instead, the design process starts with the task at hand, inspired by different conditions on site, and we try different strategies. Among these six projects, each one can represent a particular strategy. It’s not always the initial strategy we started with. In many cases, these strategies transform during the process, like in the case of the Jewish Museum, where we are showcasing the tracing. The epigenetic landscape was not initially designed the way it appears now. When we first entered the competition, we needed a complete understanding of the entire program. As the program and the different exhibition components desired for the site became clearer in the later design stages, they significantly influenced and shaped this epigenetic landscape. So, in this context, tracing became the right solution after thorough analysis and consideration of all site conditions. This is why these few projects can each represent a strategy, and it’s not always the strategy we started with; it might change or has changed.

©designboom

Lars Krückeberg continues: We never start with a preconceived form in mind. We genuinely question its necessity. The notion of signature architecture, we believe, can be very limiting. While it can be a useful tool, sometimes having a fixed idea about a particular form for one project may not be suitable for others. A self-referential and highly formal approach may work well for a museum that stands on its own in a unique context, such as in new cities in the Middle East or China. However, in the context of a European city, especially for a residential building, the surrounding context plays a significant role. We question the idea of already having a preconceived form that primarily talks about the architect and their firm rather than addressing the actual problem at hand. We want to talk about problems and find the right methods to find the right answer. By doing this, we aim to create something unique that provides a specific response to the site. This is our thesis: if you do it right, you create something unique that has the chance to have an identity, to bring something to the urban environment, maybe to be loved and hence survive.

©designboom

DB: Could you describe a project where GRAFT’s curiosity and appetite for innovation pushed the boundaries of traditional architecture and resulted in a truly unexpected outcome?

Sven Fuchs: We could talk again about the Solarkiosk. What’s interesting about this project is the concept behind it. When we say we don’t aim to be recognized as signature architects, we are dealing and identifying ourselves with the concept. The concept behind the Solarkiosk is architectural activism, and I’d like to explain this further. It’s about recognizing a specific need, feeling the urge to intervene without having a client assign a task, and creating a solution from your own intrinsic motivation. It’s an inner drive that leads you to develop an approach, and this is what the Solarkiosk represents. So, behind the Solarkiosk, there’s a manifestation of a concept and strategy. It’s not a strategy geared towards a predetermined formal solution but rather a strategy as a concept for taking action.

Lars Krückeberg: Maybe even go one step back; in the end, curiosity at its best is love. Casanova once said that curiosity is three-quarters love because, in curiosity, you don’t know what you will find. You have to be prepared and have a mindset to love the unknown, the things you don’t know. Only then will you discover new things. The Solarkiosk is a good example of this. We were building in Africa, specifically a Children’s Clinic outside of Addis Ababa. This was our first big project in Sub-Saharan Africa. While in a bar, Wolfram met a person named Recep, who later became our friend and partner. We had a rough concept of the Solarkiosk and were curious. So, we spent two months designing it and then presented the results to him. He was incredibly impressed, and we realized we had stumbled upon something significant. It’s about curiosity, not necessarily limited to sitting in a bar but sometimes finding opportunities and innovation in unexpected places, like a hotel bar in Addis Ababa.

Sven Fuchs: The importance about curiosity is maintaining a state of mind that allows you to discover something you weren’t actively looking for – that’s serendipity, and that’s kind of what we live for.

Starting in the past, often without knowing it, you begin to take steps to create something, perhaps having an idea of your potential goal but not knowing the exact path and being open to finding it. This is driven by curiosity.

image ©Erik-Jan Ouwerkerk

DB: You have been successfully producing architectural solutions for over twenty years. How has the studio evolved through this course? Is there a specific motto you are faithfully stuck to and have not changed since the studio’s foundation?

Wolfram Putz: It has always been challenging for us to answer because we’ve been told to find our way, find a signature, develop a methodology, and stick to it to become a brand. We’ve been advised to repeat ourselves and make ourselves known for something. However, as a group of individuals from diverse backgrounds with offices in various cultures and contexts, our curiosity has often led us to the point of repetition, which bored us. We constantly reinvented ourselves; sometimes it’s Genius Loci because the project asked for reinventions, and other times it’s just in ourselves, not to stand still, not to become a brand, not to do, again, what you’re good at, but go intentionally, of course, to find a new problem and a new challenge. But if you would ask us five partners, you would get five different answers, and we love it that way.

Sven Fuchs: Maybe there is one thing uniting us. And it’s not even created by us but written down by brave people ages ago. And this is the pursuit of happiness, which we are all after. And this is not describing a certain way, but best describes what drives all of us.

©designboom

DB: What advice would you give to younger architects?

Wolfram Putz: We were lucky to meet Oscar Niemeyer shortly before he died. And we asked this great old architect what was driving him. He emphasized the importance of what truly matters in life and our profession is friends, family, the people we encounter, and the unfair world we live in. And his goal was to make that world a little better. Had we lived in the Baroque era, we might have been passionate Baroque architects, but we would likely have continued to seek unconventional solutions and push boundaries. The key, as Niemeyer taught us, is to live in our time, stand on the shoulders of giants, and remain driven to contribute to positive change, whether in terms of beauty, fairness, or other things.

Sven Fuchs: Kill your idols, go on your own. Do not walk down roads where others have walked before; try to find a new way. Risk the pain, enjoy it, be curious, and find something that interests you and touches your heart and tries to grab it.

Wolfram Putz: Don’t wait too long! We sometimes think, ‘I still need to do this project in an office, and then I want to work for this famous firm for my portfolio.’ Start early; you will learn along the way and make mistakes anyway. So, start making mistakes quickly.

©designboom

©Erik-Jan Ouwerkerk

©Erik-Jan Ouwerkerk

©Erik-Jan Ouwerkerk

project info:

name: Taste is the lack of appetite

architects: GRAFT | @graft.official

GRAFT curators: Sven Fuchs, Lars Krückeberg, Wolfram Putz, Georg Schmidthals, Thomas Willemeit

modelmaker: ©Makujaku Studio

venue: Aedes | @aedesberlin, Christinenstraße 18-19, 10119 Berlin

dates: 28 October – 5 December 2023

AEDES ARCHITECTURE FORUM (22)

ARCHITECTURE INTERVIEWS (263)

EXHIBITION DESIGN (527)

GRAFT ARCHITECTS (26)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.